The Origins of Leeds Downbeat

The Emergence of Leeds Downbeat Electronic: with Moose

As part of our deep dive into Leeds’ downbeat electronic (Trip-Hop) music, we asked one of the pioneers of the city’s scene, Moose (Soundclash/ inventor of Dirt Graffiti), to share his thoughts on when he first started hearing Trip Hop in Leeds.

For more articles like this, please sign up here - no spam, just music articles and vinyl-only playlists!

“Until I first arrived in Leeds at the end of the 70s, I had only really known sugar-sweet pop, soul and disco. I had even become a member of the ELO fan club.

Moving to Leeds around ‘78 from London’s commuter belt was a pretty massive mental and physical culture shock, even as a 12-year-old. The worse thing, the absolute worst thing, was my cockney accent.

Within two years I was going to see super cool agit-pop legends like Gang of Four and hanging out in the F club seeing bands who looked and sounded like monsters. Bands that I still love forty years later.

But I wasn’t just tied in with that, and nor were lots of other people who were surfing what was an incredible era of new musical genres including hip hop, disco, punk and new wave.

It was common in those days to see gangs skirmishing in town; mods, skins, teddy boys, soul boys, scooter boys, any boys - they were the others who passionately wore their colours or scarves on their wrists or some such. They made up a big venn diagram of violence. Some people like me had a foot in several different clans at the same time, we were in the middle. Exhilarated and frightened. And fascinated.

I was going to Wigan Casino with the Leeds service crew casuals, I was going to a youth club where the scooters parked outside and both the soul boys and the two-tone brigade were both catered for under one roof, when they dropped the ska tunes the soul boys and girls gave their talc and blisters a break. And the holiest of them all, The F Club / Fan Club/ Brannigan’s, to see bands who were in or breaking out of the punk scene and being alternative or electronic. It was a landslide of music.

By the 80s. Leeds had become known as the goth and speed capital of the north though the soul and funk scene was still massive, and the all dayers were really popular. It’s amazing really how much of this all happened in different eras on Call Lane, and in what is now the Elbow Rooms.

We also had a blooming electronic scene that gave the city no 1 hits from Soft Cell. There was an underground electronic scene too, bands like The Cassandra Complex, nights at The Phono. The Sisters of Mercy.

We had The Warehouse where all the different types of music were chopped up and mixed together exotically. Man that was fun. No idea what was coming next, just that you would probably love it.

The Coconut Grove venue and a huge protagonist of the Latin and Jazz scene in the city, Gip Damnone was also starting to create a wonderful alternative to the other scenes. Gip to this day has a huge influence on the shape of music in the city.

That venue also hosted a great seventies night called The Mile High Club that gave us the Utah Saints. We had become a very eclectic place.

The radio was still a predictable and dull place, apart from the wonders like John Peel and Alice Nightingale. Its role with the initially less club-oriented downbeat scene was to become more pivotal in the 90s, while promoters tried to figure out how to program music people nodded to.

Then there were players in not so obvious places. My unsung hero in all of this musical soup sold records to the players who shaped their scenes from Jumbo Records, and we all called him Mikey Jumbo. He was turning people onto music we’d never imagined every day, every week. He was a game-changer.

What all this did was to provide the music lovers in the city of this era with a musical palette of astronomic proportions. What happened next put most of the northern cities you could think of into a creative garden of Eden as technology made it possible for those without any musical training to start chopping up and sampling anything they could lay their hands on. Leeds had a vibrant West Indian community, like probably the nation's most treasured trip-hop capital Bristol, and that might have given the city the edge over some of its neighbours. The reggae scene is the daddy of anything downbeat and dub, and it was already in the cultural DNA of the city.

So it began, and it seemed like everyone had or knew someone with an Atari sampler and was in a band. It was great time for music in general, unravelling itself and becoming an orgy of sound.

Hip hop was a very American thing and it took a while before we got a handle on it and started to make a sound of our own. Part of that was trip-hop. Eccentric cut and pastes.

The limitless sources of sampling and inspiration made the music rich and textured and seductive, incredibly diverse musical genres and subgenres and anti genres got thrown into the mixer and if you got a writing block, just head over to that great bag of pot luck; your mum or your dad's record collection - if they were Jamaican or Indian or Polish you might have some stuff nobody else had. And that’s what you were looking for. Pushing things along.

The internet was just rearing its head so at this time, the endless supply of music from there wasn’t available. Things were a bit less predictable. Manual digging. Wonderful, always will be.

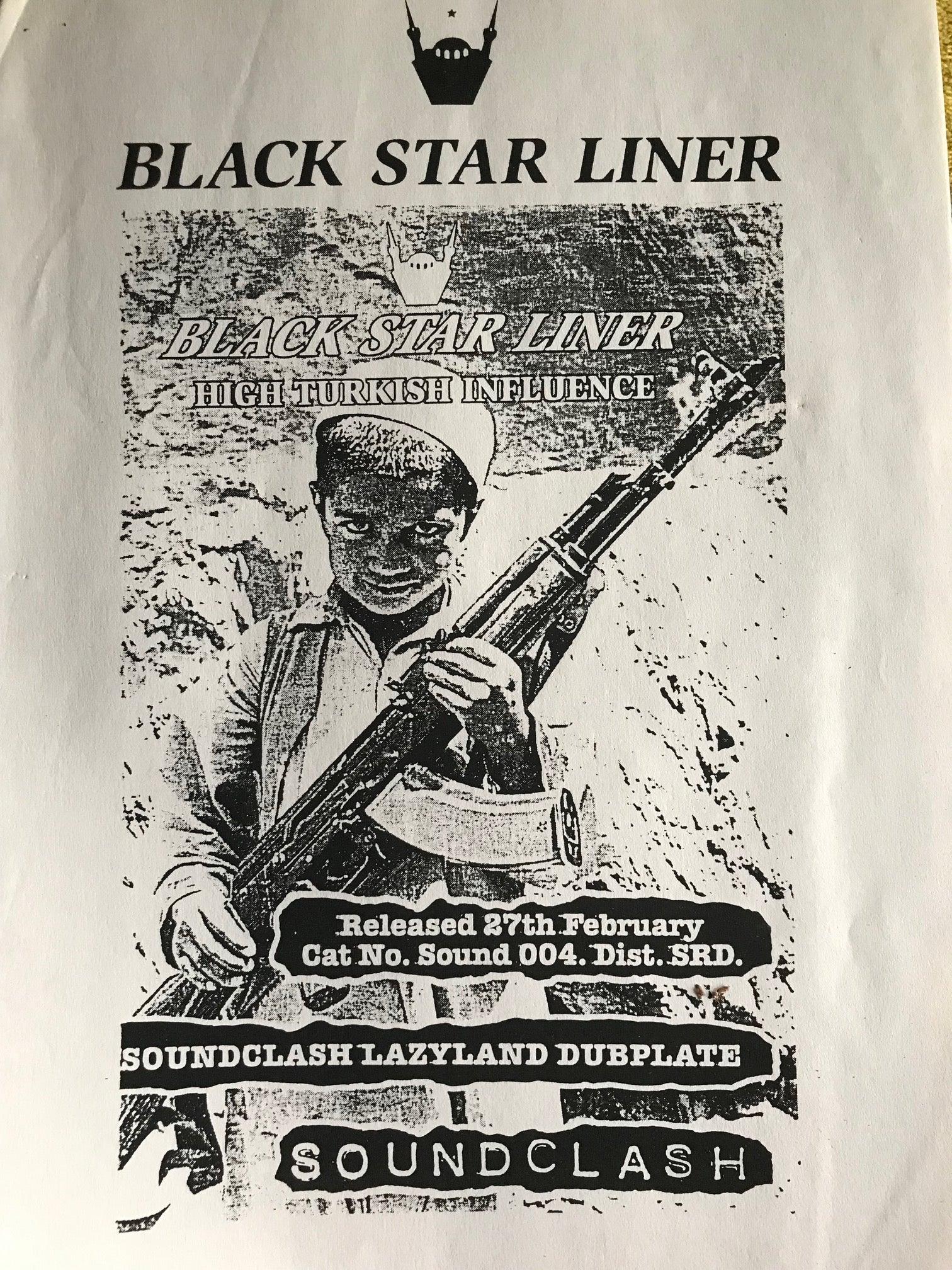

In the 90s I brazenly jumped on my good mate Chris Madden’s bandwagon and the legendary Soundclash imprint and social gatherings. Its influence was huge - Jeff Barret from Heavenly Records admits using the blueprint of the night to create one of this country’s most famous nights ‘The Heavenly Social’.

Soundclash events were a sonic masterclass that harnessed the brutal giggle-inducing heavyweight sound system of Iration Steppas with some of the most contemporary DJs that have so far existed, Weatherall being a prime example, delving into one of his lesser-known alter egos smashing out really down tempo sounds from no specific abodes. Musical orphans having their moment. It was incredible and after the main guest, Mark Ital would steal the show again. All night, that’s what happened. He would sell his records from the DJ booth, holding the anvil to tell the audience that he had three copies of that tune left, book early. The clubbers really embraced that night, it broke the mould. Downtempo music was breaking out and with it came the Soundclash label.

Pic: The Lovely Genette

At first, releasing ten-inch dubplates from Bradford’s Rootsman before unleashing Black Star Liners first releases and onto even more genre-defying artists.

The great thing about Leeds then was that if you got big you had a ladder with you for those to follow, unlike the more selfish 80s when acts seemed more inclined to leave the city behind.

In the mid-90s, a clump formed from these players joined under one roof called Junction 47 (the then last and furthest junction on the M1 from London); there was Chris Madden from Soundclash and Gip from the Cooker and Elliot Ruben and Crash Records’ Steve Mulhaire and a roster of artists that is hard to comprehend, even just in terms of the three resident guitar players in the house The New Mastersounds Eddie Roberts, Triumph 2000s Richard Formby and the soon-to-be Bedlam a Go Go’s, Chris Dawkins.

pic: Chris Dawkins

Bands were signing to Sony and EMI and Warners and it was blowing up. But things don’t run to script in that industry; in fact, the whole industry has no karma in my book. The idea was that because the industry was run by and for those around the capital, if we joined forces we would be harder to ignore and that we might move the attention away from that most sewn-up of cities - and it worked at first. It only stopped working because of bad management I think. Cash flowing too freely in the moment.

Bedlam were great. A musical Adams Family led by a star in his own right, Leigh Kenney, who still sings for Faithless as did his younger sister Rhianna who answered the telephones at J47 during the school holidays! They were both signed by Sony. Rhianna made some incredible pop tunes. I never understood how she didn’t become a household name.

Bedlam were brave, they weren’t afraid to go in any musical direction they were raw and they were stoners, they were part of a moment that was unnecessarily given some daft name by desperate music journalists like skunk rock or something. Regular Fries, another great Leeds band, would always get sucked into that genre too if it existed in the first place.

Trip-hop became terribly unhip for some reason, like the big beat thing did later, but it left with us so many utter masterpieces that it never went away really. It probably just needs renaming and repackaging, though it was such a good description, I hope it doesn’t.”

Moose

History of Leeds Trip Hop Playlist & Article